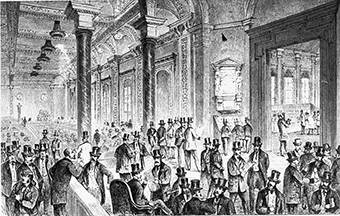

Visit to a stock exchange in Germany in 1905

"A shrill scream and shout"

It is the time of the cabs and equipment when A. Oskar Klaußmann visits the Berlin Stock Exchange. He experiences an impressive day with tumultuous events that the general public finds difficult to understand.

Berlin stock exchange around 1850

We buy the tickets

Around noon in Berlin we cross the monumental Kaiser Wilhelm Bridge and see the colossus of the Berlin Stock Exchange on the other side of the Spree Arm, almost exactly opposite the building of the New Cathedral. A conspicuously heavy traffic of hackney carriages and private teams, all of which stop in front of the large portico, tells us that the business customers of the stock exchange have begun. We buy tickets for a small fee and open the door that leads from the corridor through a short side corridor to the gallery.

Fear and curiosity

But the moment we put our hand on the door handle, we pull it back in shock. A shrill screaming and shouting of a frightening kind sounds towards us. It sounds as if a thousand people on a sinking ship were screaming in fear of death. But fear and curiosity drive us forward, in the next moment we are standing on the narrow stock exchange gallery, and a noise, deafening in the truest sense of the word, comes up to us.

Over the white marble railing we look down into a hall, in which excited, screaming people are whirling around, crowding together in groups, especially in a corner in life-threatening crowds. Hundreds, thousands of hands are stretched out in the air, thousands of people scream, and the reverberation, thrown back from the vaulted ceiling of the huge hall more than three floors high, roars in our ears like the humming and whirring of a large dynamo machine.

6,000 people

It's the same with every visitor who steps into the stock exchange gallery for the first time. It takes him some time to gather, to get his ear used to the sounds of the same storm, even to get rid of a certain feeling of fear.

The mighty hall down there, the largest in Berlin, which could comfortably seat ten thousand people, is divided into three equal parts by rows of columns, and at the bottom, between twelve and three o'clock noon and three o'clock noon, about 3,500 people move simultaneously. However, since some of them remain only for a shorter time and are supplemented by new arrivals, approximately 6,000 people travel in this hall during the trading hours.

Quiet at the product exchange

Let us first let the external impression take its toll on us! In the section to the north, whose gallery we entered first, it is the loudest, most traffic prevails.

If we continue on the long, narrow gallery at the west side of the giant building, we discover that in the second section there is an almost noble silence, and that in the third there is actually nothing going on.

This third section used to serve the purposes of the commodity exchange, which was closed as a result of disputes between the government representatives and the stock exchange people, and which was reopened only recently. It is quite peaceful here. You just don't see any talking groups, and the terrible shouting and roaring from the northern section only reaches us in a subdued but still clear enough way.

Only by verbal agreement

The term "stock exchange" originates from the 15th century in Belgian Bruges. It describes a regular gathering of rich Italian traders in the square "ter buerse". This market place was named after the local patrician family "van der Beurse" (lat. "bursa" - bag, purse).

What are the four thousand people doing down there in the stock exchange hall? The answer is: you buy and sell. They buy and sell values and securities, and the whole stock exchange is nothing but a market whose goods are not products of nature or human hand, but money. Money is bought and sold, money is traded.

The stock exchange down there is, apart from the commodity exchange, merely a securities exchange, and securities are understood to mean securities that represent a certain monetary value, i.e. government bonds, shares in mines, breweries, ironworks, transport companies, etc.

However, this securities transaction on the stock exchange is a double, an effective and a difference transaction. If someone has saved himself a certain amount of money, say five hundred marks, he tries to invest the money interest-bearing, and if he does not want to obtain mortgages that are not always available, he invests the money in interest-bearing securities. He has them bought by a banker on the stock exchange. The transaction becomes an effective one, the desired paper is really (effectively) bought, i.e. at the stock exchange however only by verbal agreement.

In the afternoon of the same business day, however, the seller sends the paper to the banker's office who bought it, and here the paper is paid in cash. Conversely, the person who needs money and who has invested his savings in securities, brings them for sale through the banker on the stock exchange to get the cash back into his hands for any purpose. This effective business turns over millions every day on the stock exchange, especially on the two largest stock exchanges in Germany, Berlin and Frankfurt. But it takes place extremely quietly, almost noiselessly.

Unsolid speculation

The difference business is quite different. This, too, involves the purchase and sale of securities by the parties involved. But both the buyer and the seller do not really want to deliver or buy the securities in question. It is only the difference at the last of the month.

Let us assume that an industrial paper stands at 140 percent, i.e. you pay 140 Marks for every 100 Marks nominal value, because the industrial paper in question pays a high dividend, and because the conditions of the stock corporation in question are very favourable. Let us also assume that I believe or suspect that this paper will rise by the end of the month. I therefore buy ten, fifty, one hundred shares of the paper in question from another visitor to the stock exchange at a price of 140. If, at the end of the month, the price of the paper is 150, the other one has to pay me the difference between the prices of 140 and 150, in other words 10 Marks, in cash. If the paper has fallen to 130, he has to demand the difference from me. Because of the payment of this difference, the transaction is called a difference transaction, and in this kind of transaction lies the unsound speculation, lies the stock exchange game.

Monstrous screaming and roaring

Now let's go down from the gallery to the street at the water's edge and then enter the Börsenhalle itself through the huge colonnade entrance! The entrance is exceptionally permitted by the elders of the merchant team and the stock exchange board. Otherwise only the people who have registered with the board of directors and who pay for the permanent visit have access.

We go to the left into the cloakroom, and here the uniformed stock exchange servants take off our overcoats, hats and canes. These stock exchange servants are specialists and memory artists. They have the outward appearance of all 6,000 stock exchange visitors in their heads in such a way that they know at first glance whether the person entering is entitled to enter the large stock exchange hall or not.

While we are getting rid of our clothes, the helping stock market servant tells us: "Discount 193.80, was on 194, went down to 193.60 and has recovered 80." By "Discount" we mean the shares of the Berliner Diskonto-Kommandit-Gesellschaft, which form one of the main speculation securities, and at the price which the servant informs the newcomer when the overdraft is taken off, the stock exchange operator knows whether a quiet or a lively stock exchange is taking place.

Today it is a quiet stock exchange, which the layman who comes from the gallery above and who has been constantly ringing his ears with the outrageous screams and noises doesn't really want to believe. We strike back an enormous porter and the next moment we are in the thickest stock market turmoil. The screaming is ringing in our ears again, only now quite different from above in the gallery. The humming and buzzing of the sound reverberation disappears, but people shout the prices directly into our ears.

If we sit down quietly for a moment, we are immediately gripped by a wave of people that floods past us, packed, whirled around us, and in a minute we breathe a sigh of relief in the second trading room, where on benches whose backs are on metal plates bearing company names, dignified older and younger gentlemen, the bosses of the big houses, sit.

If Transvaal news doesn't come out, it will be very quiet again.

A well-known stock market journalist gets in our way, and he shouts and says: "Nothing going on today, very quiet stock market. If news doesn't come out of Transvaal, it'll be very quiet again." In one of the rooms available to the press for their work, where it is much quieter than out there in the hall, our friendly guide quickly gave us some unavoidably necessary explanations.

"They don't dare to go today," he says, "neither the Haussiers nor the Baissiers. The arbitrageurs are also waiting to see what will happen, and London has only been bought for a short time because a penny has gone down. London announces that New York has also good prices from yesterday evening."

Haussiers and Baissiers

However, this has given us an exhaustive description of the current situation on the stock market. Unfortunately, we do not understand what is being said to us and we ask the gentleman from the stock exchange press to translate his technical terms, which are the essential material for the stock exchange report of the newspapers, into his beloved mother tongue. "The current market value of a security is called its price. It can go up or down, it is said that the securities go up or down.

The people who expect and speculate on the rise of the price of one or more securities are the bulls - the speculators who expect the fall are the bearers or counter-mineurs. Arbitrageurs work not on one, but on several stock exchanges and take advantage of price differences by buying on one stock exchange and selling on the other.

This is done by telegraph or telephone. In the basement of the stock exchange building, there are about a hundred telephone cells available to stock exchange visitors, as well as a special telegraph office, which is directly connected to all stock exchanges in Europe and which processes many hundreds of telegrams during the hours from twelve to two o'clock at noon. "Short London" means short-sighted bills of exchange to London, i.e. bills of exchange that are due within a short time, short London e.g. within eight days. On the stock exchange, bills of exchange are also traded at foreign bank locations. Such bills of exchange are effectively bought by people who have to make payments in the country concerned; however, time or difference transactions can also be made in long-sighted bills of exchange in Brussels, Amsterdam, London, Petersburg, Vienna, Scandinavian, Swiss and Italian banking centres.".

In the Montan corner

Let us go back into the Chamber now and let us have more explanations!

"What does the constant turmoil in the corner of the first Chamber mean? What do the people who scream and gesticulate like that want?

"This is the Montan Corner, where the main speculation papers in mining and metallurgical stocks are traded. Since the stock market is rather listless because of the uncertain news from Transvaal, the speculators are particularly concerned with the mining stocks. As you can see, the crowd in that corner is around a table surrounded by barriers.

The gentlemen standing at the table are sworn brokers. All the effects are divided into groups, and for each group a broker is appointed. These sworn brokers (also called mustards) are the official business intermediaries. They buy and sell, and the supply and demand they receive determine the current market value, the price of the security in question. They hear the brokers announce the prices they receive for the security in question as a result of supply and demand. On the other hand, the stock exchange people standing around the tables call the prices at which they want to buy or sell".

Five outstretched fingers

"But why are all these people around the barrier raising their right arms?"

"They use their hands to make themselves understood more quickly. If they wave their hands towards the broker, they indicate that they want to sell him, they wave their hands towards themselves, they want to buy. By the number of the lifted fingers they indicate, around how many "posts" the business should go. By "item" one understands the usual unit amount for time transactions. Each sale or purchase always involves a certain, rounded amount or a multiple of such an amount. Thus, for example, English-Russian bonds are only traded in items of 1000 pounds sterling, while railway, bank and industrial securities are only traded in items of 15000 marks. Five outstretched fingers thus mean five times 15000 Marks of the industrial paper in question".

"And does the broker know who all the people are?"

"Of course, the brokers know all the businessmen personally. They also know the employees of the big houses who place orders here for their bosses. They see the bosses sitting quietly in their seats. The gentlemen constantly receive dispatches or news from their employees and have the latter buy or sell, either for themselves or for their customers."

"They said earlier: London announces. Do the other stock exchanges also have influence here in Berlin during business hours?" we ask our guide.

"Certainly, and a very significant influence. London and Paris, followed by New York and Vienna, have the greatest significance for Berlin. Because of the time difference with America, it's not exactly stock exchange time in New York when the stock exchange in Berlin is open, but the New York prices of the last stock exchange have an influence here, but even more so the "mood" in London and Paris. Even if the local stock exchange is at first business-minded and firm, it fades when "matt London" and "matt Paris" are reported. Even if the speculators do not know why the foreign stock exchanges are out of tune, they fear that something bad and dangerous is in the air."

Speculators who spin

Our companion has been called to the trading floor, and we follow him. Bad news for England has arrived from Transvaal. Nobody knows if this news is true. But the English papers, especially the Goldshares (shares in the South African gold mines) fall immediately. Shortly thereafter comes the news that the London Stock Exchange has fallen. So the bad news seems to be true; speculators are losing millions.

"Is there no salvation for the speculator at such moments?

"He can "turn", as the guild expression says. In such a case, if he has speculated á la hausse, he can suddenly speculate á la baisse in order to earn what he loses in the bull market. But the "turning" is also a dangerous thing, the right time for it is sometimes over in five minutes, and only those who are present here in the hall can seek help in this way; the small speculator in the province is lost in such a case."

Between the pillars on the two long walls of the hall there are niches which, as we are taught, are rented to the big banks for heavy money. Here sit the directors and authorized signatories of the banks with their stock exchange staff, here intermittently the dispatches arrive, and from here the instructions for purchase and sale go to the brokers.

Much worse than Monaco

It is soon two o'clock, we want to leave the stock exchange, as at two o'clock the official stock exchange closes; the unofficial one lasting until three o'clock, and if by then eager businessmen do not want to leave yet, they are "rung out" by the servants.

This was our first visit to the stock exchange, and we want to make do with it. From that one visit, however, the reader, who has participated in it in spirit, may take along the firm intention not to play on the stock exchange, i.e. to speculate. The difference deal is much worse than Monaco and for the speculator, who does not go daily to the stock exchange, it is almost a folly.

June 2019, © Deutsche Börse AG